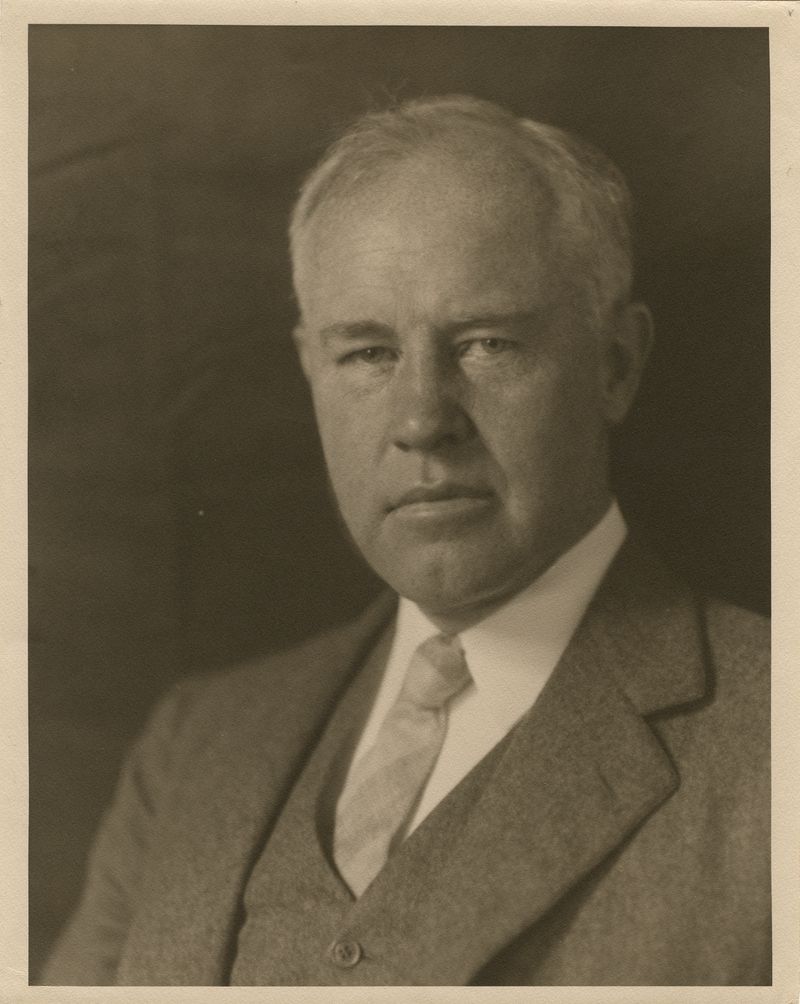

Director of Medical Sciences, 1930-1945

Alan Gregg was forty years old when Max Mason asked him to return to New York as head of the Rockefeller Foundation's Medical Sciences Division. Even though Gregg thought himself a little young for the position, he did have impressive credentials: a Harvard MD, incomparable knowledge of the leading medical research and teaching in Europe, and field experience with the International Health Division, which had given him insight into the workings of the foundation's public health activities. Moreover, Gregg was an "old hand" compared to Mason and the other officers hired for the new divisions--Social Sciences, Humanities, and Natural Sciences--created by the 1928 reorganization. He was thus well prepared for the challenges he faced in the new post. His responsibilities were greater than Pearce's had been for the former Medical Education Division, because he took over the programs in U.S. medical schools, plus there was new research to be supported. The opportunities to affect medicine around the world were substantial, but the economic Depression and new reorganization quickly put limits on Gregg's ambitions.

Gregg disliked the foundation's new direction following the reorganization, in particular, the policy of granting more numerous shorter-term grants. Although a rational response to the decreased value of the foundation's holdings during the Great Depression, this change was, in Gregg's view, unwise and shortsighted. In a March 1930 memo, he worried about the "danger of being in the thick of thin things." The temptation to expand the number of new grants without adequate study and reflection upon their ultimate goals not only made new projects less likely to succeed, Gregg concluded, but also limited the foundation's ability to observe and assess the effectiveness of current programs. Reflecting on his own experience as a field officer, Gregg spelled out the specific consequences of administering many small projects rather than fewer large ones. ". . . [the] pressure of correspondence, of small details, of many visitors and, not least, of frequent field trips in which almost every minute is taken, reduces to a very great extent the opportunities for solid reading, careful discussion, and reasoned reflection upon the validity and usefulness of our activities, and their adaptation to the various conditions we meet."

While Gregg agreed with the trustees about the limits of the foundation's resources, he drew the opposite conclusion, arguing instead for substantial, long-term support of selected institutions rather than the awarding of numerous small research grants. He had accepted the post of Medical Sciences Division director intending to correct this new policy. Although the tactic failed in the long run, a compromise did allow his division to devote resources to a new field of medicine: psychiatry, along with the related fields of neurology and psychology.

At a special trustees meeting in April 1933, Gregg discussed the "History and Future Program" of the Medical Sciences Division and argued for special attention to the "sciences underlying psychiatry." He defined these sciences broadly, including "the functions of the nervous system, the role of internal secretions, the factors of heredity, the diseases affecting the mental and psychic phenomena of the entity we have been accustomed erroneously to divide into mind and body." Gregg did not propose such studies because of their immediate prospects for success; in fact, he bluntly admitted that these were not areas "in which the finest minds are now at work, nor the field[s] intrinsically easiest for the application of the scientific method." But this, he argued, was the very reason to support psychiatry and neurological science, "because it is the most backward, the most needed, and probably the most fruitful field in medicine."

In the 1930s, Gregg's Medical Sciences Division supported the creation or expansion of psychiatry departments in major U.S. medical schools and in several British hospitals. He also arranged the long-term support he favored for a few select projects, including the creation of the McGill Neurological Institute in Montreal under Wilder Penfield. Gregg supported short-term research projects, but many resembled senior fellowships, such as support for Hugh Cairns in neurosurgery in England, Elton Mayo's health hazards study at Harvard, George Draper's work on constitutional medicine at Columbia, Leonard Colebrook's testing of the new sulfa drugs at Queen Charlotte's Hospital in London, and Henry Dale's work on viruses in London.

Gregg's correspondence shows how well regarded he was by his peers and staff. For example, both Peking Union Medical College's Roger Greene and Elizabeth Crowell (who was in charge of developing nursing education at the Rockefeller Foundation), though rather far removed from Gregg's supervision, took time to write him about their concerns and praised his advice. As one of the few women in a high position at Rockefeller, Crowell's praise is especially noteworthy. Although Gregg was hardly a feminist--in fact, he very much mirrored his age of "men of medicine," and his jokes and stories were in the "old boy" tradition--Crowell repeatedly wrote that he was one of the few men in the organization who appreciated her efforts. His assistants in Paris also wrote touching letters, and as he had done in France before the German invasion, Gregg revived his writing of a general letter to family and friends, describing conditions observed during his travels and his reflections. He had first done this when he went to France in 1924, and he sent several more in 1939 and 1940 under the heading "Table d'Hôte." As interesting as the contents were, the names on the address list suggest that Gregg had a way of becoming close with work acquaintances, for in addition to family and personal friends, they included a number of foundation colleagues and grantees.

The beginning of World War II had major repercussions for Gregg, halting the foundation's work in Europe and eliciting his pacifist and isolationist views while the United States remained neutral. After the U.S. entered the war, Gregg focused more on postwar plans than on specific research projects.